A Life Well Lived: A Review of Rachel Heng’s SUICIDE CLUB

This review was originally posted on my blog in 2018.

This review was originally posted in my blog on July 15, 2018. It's been lightly edited.

Would you want to live forever?

In her debut novel Suicide Club, Rachel Heng reaffirms the notion of “be careful what you wish for” and challenges her readers to reflect upon the price they would pay for immortality.

We live in a world where the quest for long life is a multimillion-dollar industry. In Heng’s near-future setting, people live for hundreds of years. But at what cost?

In this engaging story, Lea Kirino is a successful woman with the potential to live forever. By all accounts, she has a profitable career, a loving relationship, and a comfortable apartment.

They burst out laughing. Todd laughed too, right on cue. Their laughter was rich and cascading, a golden ribbon unfurling through the party, making people turn to look, people who were until then perfectly secure of their position in life but at that moment felt something was missing. (page 7)

Lea follows all of the suggested guidelines for nutrition (juicing), exercise (low impact, including no running), and avoiding stress (even too much smiling causes unwanted wrinkles).

It wasn’t often, these days, that things broke anymore. Everything was toughened, reinforced, enhanced. You really had to try to break something. (page 132)

Then, one day, she sees her estranged father on the street, and it changes everything. Lea begins to question being a “lifer” as she is confronted by the divergent and illegal ideas of her father and the mysterious Suicide Club.

The Suicide Club is made up of people who challenge the status quo that immortality – and the price one pays for it – is a worthwhile goal. The members are committed to exercising autonomy and control over the course of their lives: to eat what they want, live how they please, and die how (and when) they choose.

“Something has to change. In being robbed of our deaths, we are robbed of our lives.” (page 2)

Lea begins to question everything she thought was true and right. Heng challenges her readers to consider issues of longevity, family relationships, wealth and consumption, and what truly makes life worth living – and dying. For me, it brought up contemplation about the right to die with dignity and autonomy, though not specifically taken on in the book.

One of the strengths of Heng’s writing – and there are many – is her commitment to detail. Her ability to describe this world is rivaled only by her presentation of it; while she is descriptive in her storytelling, Heng also trusts her reader to put the various pieces together. She takes her time and brings the reader into Lea’s world day by day. The result is a dynamic, multidimensional setting and intriguing characters that set the stage for the readers’ reflections.

Lea felt a heaviness in her lower back, as if the weight of all their problems, all their pain, had crept into her body, wrapped itself around the base of her spine, settled there. Calcified, anchored, immovable. (page 274)

Suicide Club is a thought-provoking novel perfect for readers who like dystopian or speculative fiction that makes you think. I was both entertained and intrigued by the book; it held my interest throughout. With characters you will relate to and a story that will draw you in, Suicide Club is one of the strongest debuts of the year.

Find Rachel Heng online at https://www.rachelhengqp.com/ and on Twitter @rachelhengqp.

For further reading:

- Five Questions with Rachel Heng by Megan Leigh for Breaking the Glass Slipper

- Letting Go of What We Love: Talking With Rachel Heng by Kristen Iskandrian for The Rumpus

- Rachel Heng talks about her debut novel Suicide Club – Sceptre (video) for Hodder Books

- Suicide Club review on Kirkus

- Suicide Club: What if burgers and beer were illegal? by Annabel Rackham for BBC

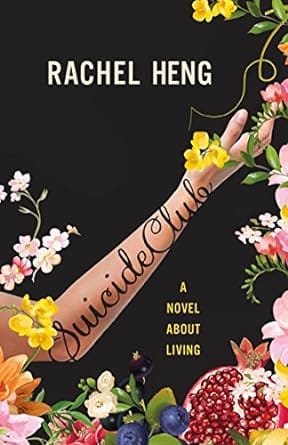

Title: Suicide Club: A Novel About Living

Author: Rachel Heng

Publisher: Henry Holt

Pages: 352

Publication Date: July 10, 2018

My Rating: Highly recommended

Content information (potential spoilers): Animal cruelty (pp. 100-103); several descriptions and discussions of suicide; bullying and violence (pp. 177-181); self-harm (p. 98); descriptions of sickness, hospitalization, dying, and death; family estrangement and death; sex (pp. 278-280); murder.

Disclosures:

I received an advance reader’s edition of this book from the publisher in exchange for an honest review. Thank you to Henry Holt, Declan Taintor, and Rachel Heng. This review contains affiliate links. Please support independent booksellers.